Date of Issue:February 7, 2019

・Activity 1/City Night Survey:Rio de Janeiro/ (2018/10/13-10/23)

・Activity 2/TNT Forum 2018 in Santiago(2018/10/17-10/18)

City Night Survey:Rio de Janeiro/ Santiago

2018/10/13-23 Mikine Yamamoto + Kouki Iwanaga

This was our first South American survey in about 15 years. We tracked the light expression of Rio de Janeiro, a port city marked by both entertainment and poverty, which hosted the FIFA World Cup in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016 and has become increasingly international. While possessing famous coasts like Copacabana and Ipanema and being counted as one of the world’s three most beautiful harbors, it also has the “favela” slums covering its hillsides. Surrounded by magnificent nature, Santiago, Chile’s largest city, has annual rainfall of only about 360mm, meaning it is sunny for most of the year. We investigated the lighting situation of this city blessed with natural light.

The nightscape from Pão de Açúcar: A beautiful contrast created by the rich topography

Viewing Copacabana Beach from Pão de Açúcar

Favelas built on the mountain slopes

■Rio de Janeiro / Brazil

Rio de Janeiro is an international tourist city that hosted the Carnival and the Olympics in 2016. It is said to be a microcosm of the country, where light and darkness coexist: scenic areas with beautiful topography blending nature and culture are situated next to slums. We surveyed the light expressions of this city, which has various faces, including the glamorous light of tourist and resort areas, and the strangely glowing light of the favelas (slums) where poor communities gather, reflecting the lives of the people.

The suburbs leading from the airport to the city center have a typical streetscape, similar to those in China or other parts of Asia, and abandoned-looking buildings are prominent. A notable feature is the huge number of small buildings (favelas) that completely cover the mountain slopes, creating a unique landscape. In Centro (the old town), historical and modern architecture coexist, and there are streets, squares, and buildings that were redeveloped for the Olympics. Copacabana Beach is lined with hotels and restaurants and is bustling with tourists. The overall atmosphere of the city, perhaps due to the bad weather, was completely devoid of the cheerful, passionate feeling we had imagined.

■Nightscape Emerging in the Valley

Pão de Açúcar (Sugarloaf Mountain) is the iconic rocky mountain that defines Rio de Janeiro’s nightscape as it juts out into Guanabara Bay. From its 400-meter-high summit, you can see the entire city of Rio de Janeiro, nestled between the mountains and the sea. The deep valleys of the rugged mountains are tightly packed with buildings, creating a stunning urban view shaped by its unique topography. As evening progresses, the mountains and sea fade into shadow, and the city’s lights emerge. The overall impression is one of low light, mostly composed of streetlights and window lights, with no buildings featuring garish illumination. The lights of the favelas (slums) blanket the mountainsides, their dense, fine points of light creating a three-dimensional, slightly mysterious atmosphere of life. The beach lighting is notably bright and catches the eye, its reflection on the ocean surface emphasizing the beautiful curve of the coastline—a signature feature of Rio de Janeiro’s nightscape. With better weather, the Christ the Redeemer statue on Corcovado Hill would have been brilliantly illuminated, offering an even more iconic view, but unfortunately, we couldn’t see it from the city at all during this trip.

The beautifully curving Copacabana coastline.

Copacabana bars bustling with foreign tourists.

Carioca Street where there is no sign of people

The Light-up of the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Theater

The plaza in front of the Municipal Theater. The number of pole lights is extremely high

Museu do Amanhã. The exterior wall with solar panels installed

Rodrigues Alves Avenue (Daytime)

Rodrigues Alves Avenue (At night)

At night, the lively atmosphere of the day completely disappears, and the streets become quiet with no sign of people. Police vehicles are stationed in various places, and their lights are extremely conspicuous. In the old town (Centro), historically important buildings and churches are lit up. The technique is common, where floodlights are installed on the streetlights for the roadway to uniformly illuminate the entire building. In the downtown area, shops are closed and there are no people around. There are no sign lights whatsoever, and only the roadway streetlights illuminate the buildings. In the park within the development district, which was redeveloped for the Olympics, a large number of pole lights were installed, making it a very bright park with an average of over 30 lux.

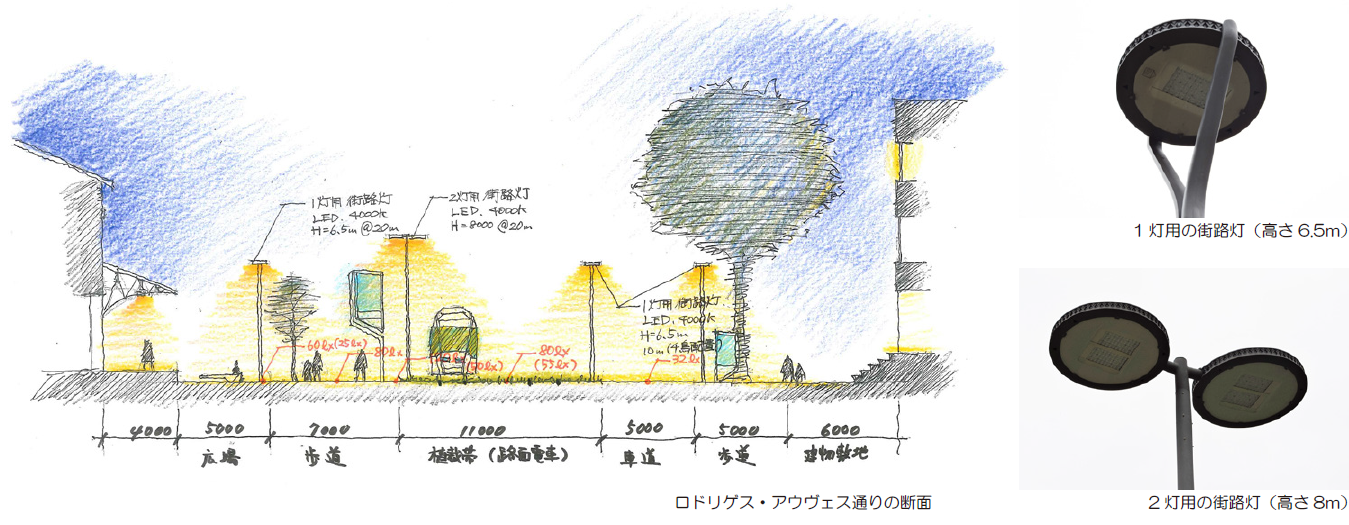

Rodrigues Alves Avenue was also developed for the Olympics, resulting in a comfortable space that is 23 meters wide and offers clear visibility. The center of the street is a planting strip where a modern tram runs, and both sides are separated into a roadway and a pedestrian space. LED streetlights are used, and the design of the two types of streetlights is unified. In the 7-meter-wide pedestrian space, 8-meter-high, two-fixture lights are placed at a 20-meter pitch on the central planting strip side, and 6.5-meter-high, single-fixture lights are placed at the same pitch on the building side. The illuminance in the center of the pedestrian space is 80 lux, and 25 lux in the darkest areas, making it extremely bright. The buildings along the street are offices converted from warehouses and are lined up continuously. Since the walls are illuminated, there is a sense of brightness, creating a very comfortable space. The roadway side has a staggered layout of 10-meterhigh lights, with an illuminance of about 35 lux in the center of the road.

The urban lighting in Rio de Janeiro has become light aimed at preventing crime by making things bright. Because we couldn’t feel the presence of people, there was no sense of ease or safety; an air of tension permeated the area. I was reminded that the beauty of a nightscape is truly created by the people active in that place and the atmosphere they generate. (Mikine Yamamoto)

■Santiago / Chile

Santiago is the largest city in Chile, surrounded by the Atacama Desert, the Patagonian Ice Field, Aconcagua, and the vast Pacific Ocean. With climatic conditions that bring over 300 sunny days a year, we investigated the relationship between the city and its natural light. We also surveyed the urban lighting conditions of Santiago—a major city that still offers tranquility with its many museums dedicated to pre-Columbian artifacts and its abundant nature, such as forest parks—as well as the interest in light shown by the people who live there.

The Sky Costanera Center, the tallest building in South America, with Aconcagua towering in the background

The view from the Sky Costanera Center. The old town is on the left, and the new town is on the right

Spotlights used to illuminate the ornamental pillars of a historical building

Illuminating the building’s structure with floodlights to make the entire building glow

■Light of the Old Town and Light of the New Town

Looking down at the Santiago cityscape from the observation deck of the Sky Costanera Center—at 300 meters, the tallest building in South America—there were two distinct expressions of light. One was the old town, scattered with the warm glow of sodium streetlights, and the other was the new town, bathed in 4000-5000K light that uniformly illuminated the streets cutting through the highrise buildings. Walking through the streets, we observed that the old town often used external illumination to light its historical buildings, while the new town featured modern facade lighting that illuminated the buildings from within.

■La Moneda Palace and the Entel Tower

When we visited the famous La Moneda Palace at night, we were surprised to find that, unlike other tourist spots, its main facade was not illuminated at all. The Plaza de la Constitución behind the palace had no lighting fixtures within the plaza itself; instead, the entire space was uniformly lit by 15-meter-high floodlights. The light level was about 0.2–0.5 lux on the ground and about 2.0 lux on the vertical plane,

with enough lateral light spill to faintly illuminate the palace’s rear exterior. Across from the palace, a huge Chilean flag was waving in the night breeze, lit by uplights from the ground, which conveyed a sense of dignity. However, when the surrounding buildings were illuminated by the intensely colorful signage lighting of the Entel Tower, which stands about 300 meters away, even the accompanying Santiago lighting designers and students expressed disappointment. It seems that the shared value of distinguishing between what should be lit and what should not, and the discomfort with the aggressive brightness of signage lighting, is common in Santiago as well.

■Santiago’s Blue Moment

Santiago, which was entering early summer with its Mediterranean climate, had a long blue moment, lasting from 7:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. In the evenings, the city was filled with people enjoying happy hour at the open-air terraces. While LED streetlights were widespread in the old town, many had a color temperature of 3000K or lower. I felt this might reflect the aesthetic sense of the people of Santiago—slowly savoring the blessings of nature under the warm-toned light that looks beautiful against the blue moment. (Kouki Iwanaga)

The Moneda Palace facade, standing solemnly in the darkness

The brightly illuminated Entel Tower and the lit-up Chilean flag with strong luminance

People enjoying happy hour

TNT Forum 2018 in Santiago

2018/10/17 Noriko HIgashi

The Lighting Detectives World Forum was held in Santiago, Chile, marking the first time the event has taken place in South America. Twelve core members of the Lighting Detectives from around the world gathered to exchange opinions with local lighting designers and architects. Together, we identified the problems and merits of Santiago’s lighting environment and discussed potential solutions.

Group photo taken at the Chilean National Museum, the venue for the talk event and orientation

The 14th Lighting Detectives World Forum was held over two days, October 18th and 19th, in Santiago, Chile. As the first forum to be held in South America, it attracted a large number of working professionals. Unlike previous student-focused forums, this one was centered around professional lighting designers and architects. The theme was “Lighting Heroes and Villains in Your City.” The forum began with a relay talk by core members on this theme at the Chilean National Museum and concluded with presentations on proposals for improving the lighting environment of Santiago City at the University of Chile campus.

A look at the orientation session

Acharawan, a Bangkok-based lighting designer

Everyone covering their eyes from the dazzling light

Constitution Plaza behind the Presidential Palace: Discussing whether this level of brightness is appropriate

Day 1:Thursday, October 18

■Relay Talk @ Chilean National Museum

Under the theme “Lighting Heroes and Villains in Your City,” core members of the Lighting Detectives reported on the conditions in New York, Taiwan, Hamburg, Stockholm, Belgrade, Singapore, and Bangkok. In a short time limit of just under seven minutes each, they discussed the lighting problems and attractions that their respective cities face.

■City Night Walk

The participants split into groups and conducted a Night Walk Survey through five distinct areas. Since it didn’t get dark until after 8:00 p.m., each team headed leisurely to its starting point. Some teams took the time to have a light meal and introduce themselves, while others apparently got a bit too excited with beers in hand even before the official walk began.

◇Team A:SANTA LUCIA

Team A began their Night Walk Survey from the top of a hill located in the center of Santiago. They discussed the lighting of the National Library and its surroundings along Santa Lucía Avenue. Walking along Cerro Santa Lucía and Victoria Subercaseaux Street, they were overwhelmed by the number of lighting villains. The most dominant elements in the light environment were the intense glare from fixtures installed in the park and the enormous LED screens displaying advertisements.

Although the lighting villains were more noticeable than the heroes, they found many heroes upon entering the cozy streets of Lastarria and GAM. They walked through the Cultural Center GAM to look for areas where lighting could be improved. The Night Walk Survey concluded with an interesting discussion about the area’s top hero, which was hidden inside an old building. (Aleksandra Stratimirovic)

◇Team B : Parque Forestal Area

Parque Forestal is a park located in the historic center along the north-south axis leading to the Mapocho River. Our group waited for the sunset while having a light dinner and then started our Night Walk Survey from the center of the park.

The park’s lighting mainly consisted of two types: “lantern” lighting and very tall (15m) floodlights (which we referred to as “tennis court lights”). We found it difficult to find lighting heroes because of the severe glare from both types of fixtures. However, in one spot where the park lanterns were installed on a vertical surface, they created a flower-like light pattern on the ground, which was an unexpected hero.

The “tennis court lights” were destroying the surrounding environment with their intense glare. While we completely understood that they were placed for safety reasons, the majority opinion was that more consideration for glare was needed. We were surprised that many people were using the park—playing with friends on the benches and lawns—despite it being a very cold night. It seemed people didn’t pay much attention to whether it was bright or dark.(Lisbeth Skindbjerg Kristensen)

◇Team C:HISTORICAL CENTER

Our Night Walk Survey area stretched from the historical Plaza de Armas to an area where new street art development is taking place. We first focused on the Tribunales de Justicia (Courts of Justice) and the adjacent buildings. Participants closely observed people’s behavior, paying attention to space and light—especially the light’s position, color, intensity, and distribution. From there, we identified lighting heroes and villains, discussed the reasons behind our choices, and debated ways to improve the situation.

Next, we moved to a park where, instead of enjoying the moonlight and shadows, intensely glaring light fixtures illuminated empty benches. While we understand the need for safety at night, we felt this dazzling light was not meeting human needs. The consensus was that the reflected light from the surrounding walls provided sufficient illumination. (Acharawan Chutarat)

◇Team D:Moneda Palace Area

We conducted a Night Walk Survey of the government office area, which included the two plazas flanking the official residence of the President of Chile, the political center of the country. The area was characterized by a stark contrast between light and dark: the Constitution Plaza behind the presidential palace was brightly and uniformly lit, while the plaza in front of the palace and the palace itself were completely dark and unlit. The huge national flag, a national symbol, was nominated as a villain because only the pole was glaringly illuminated by white light. It was also striking to see the heavy walls of the government buildings dyed by the light from the advertising display of the distant television tower.

Many questions were raised about why the bronze statues scattered throughout the plaza were left to sink into darkness and were not lit up. The area showed a lot of potential for improvement, and many suggestions for solutions were brought up during the walk. (Noriko Higashi)

◇Team E:Paris-Londres District

Team E was assigned the alleys around the San Francisco Church. The narrow streets, which still have the atmosphere of the old town, are equipped with classic streetlights. The low-colortemperature light from the sodium lamps illuminates the buildings, enhancing the ambiance. There were people enjoying meals and drinks in this area. However, that light was also impacting the interior spaces of the houses and hotels, leading to it being nominated as a villain. (Mikine Yamamoto)

The discussion about heroes and villains continues

The University of Chile, the presentation venue

Day 2

■Group Discussion

The groups discussed the heroes and villains of the areas they walked the previous day, explaining the reasons for their judgments and summarizing their proposals for improvement. This was an intensive session, lasting about five hours, during which they defined the heroes and villains, deduced why the lighting environment was the way it was, and formulated improvement plans.

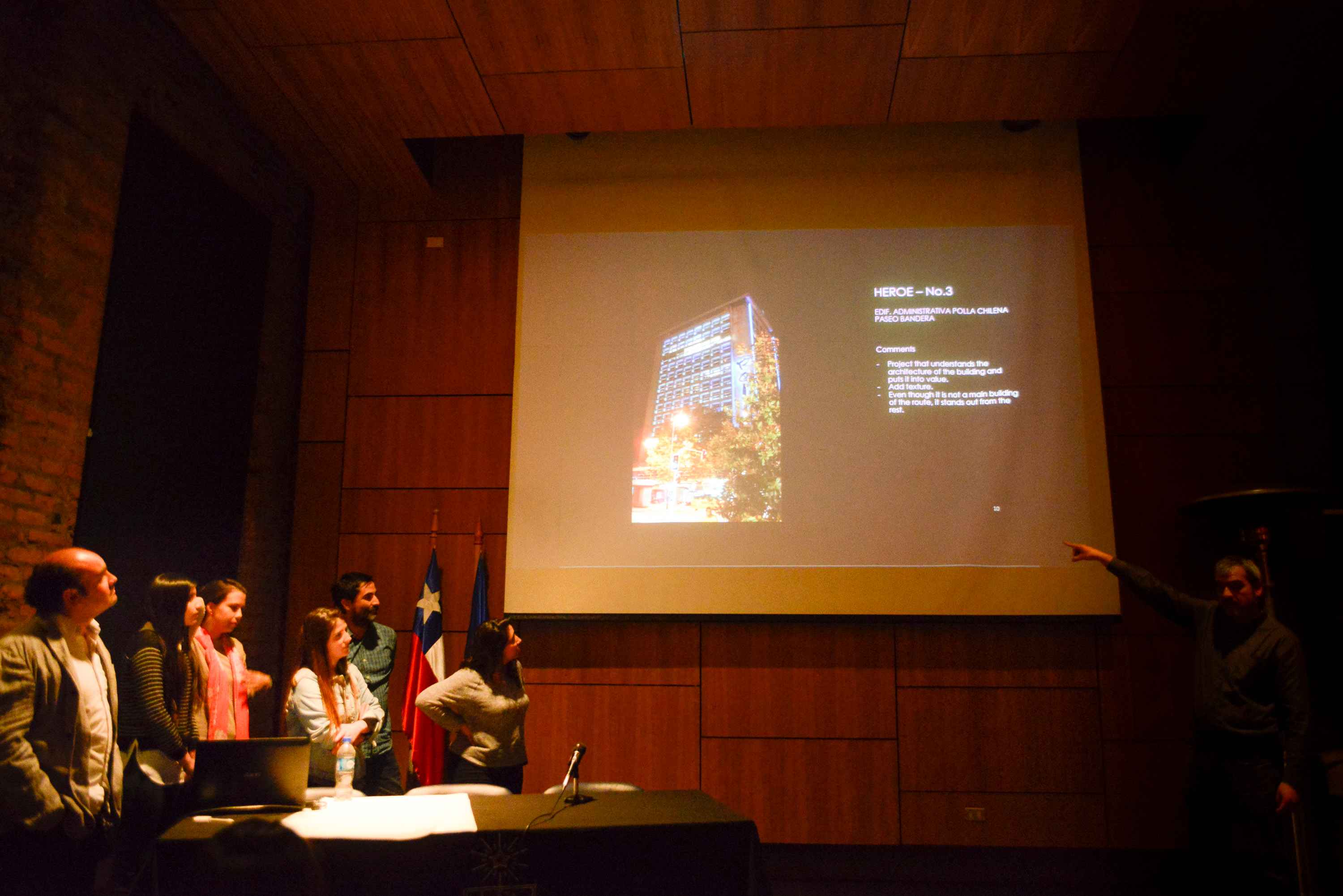

■Presentation @ University of Chile

The presentations on “Lighting Heroes and Villains” and proposals for a better light environment were given by each group at the auditorium of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of Chile. The proposals, which were developed through intensive discussion between students knowledgeable in lighting design and professional lighting designers, were showcased in elaborate presentations that included CG renderings and sectional sketches. It was a shame that the presentation time was short and there was no time for feedback from the Lighting Detectives core members. However, we were very pleased to hear feedback from the participants, who commented that their “perspective had changed” and that they “wanted to continue this kind of activity.”

Even though it’s only an annual event, gathering Lighting Detectives members from all over the world to discuss lighting with locals is definitely an activity we should continue. Now that the 14th forum is complete, we have numerous records and materials that have been sitting unused. Our plan is to organize these properly and make them readily accessible for everyone to view. (Kouki Iwanaga + Noriko Higashi)

The venue was completely full.

Each group presented their improvement proposals