Date of Issue:3 February, 2020

・Activity 1/Sydney Lighting Survey(2019.09.19 – 2019.09.21)

・Activity 2/Tokyo Survey Tsukuda・Tsukishima(2019.11.18)

Sydney Lighting Survey: How Sydney CBD glows at night

2019.09.19 – 2019.09.21 Momoko Muraoka + Sunyoung Hwang

Sydney, a capital city of New South Wales is famous for its beautiful beaches and iconic Opera House.

It makes it to the most populous city of Australia with more than 5.2million population. The climate of Sydney is subtropical with no extreme seasonal differences.

Highly saturated clear blue sky, lush greeneries, beautiful waterscape, and iconic Opera House – Sydney is the city that has it all. It is quite a lovely place to be and usually makes it to the top rankings for the most liveable cities in the world.

This time, Lighting Detectives flew to Sydney to find out how it lights up at night as a famous tourist destination. The survey focuses on the Sydney CBD (Central Business District) area. When looked down from the Sydney Observatory, the city did not have much of the façade lighting. Many of the buildings were glowing with their interior lights. There were not much of RGB lights nor media facade light except few areas of Darling Harbour and Pitt Street, the shopping district.

The shot taken from North Sydney to have an overall view of Sydney CBD with iconic Opera House and Harbour Bridge shows this more clearly. Sydney seemed rather classic with a warm tone of lighting on these iconic features and minimum architectural lights.

Interview with the city of Sydney

Interview with Laurence Johnson from City of Sydney

On the first day of arrival, we have met up with Laurence from Public Domain Strategy department from the City of Sydney to ask about Sydney lighting design direction and vision. Starting in 2000, Sydney has a lighting code that controls the night-time illumination of the buildings. Although Sydney does not have a masterplan that overlooks the Sydney CBD in general, important districts of CBD area has its lighting masterplan, and the city of Sydney is developing and updating more of those. The city is also looking into having more of the façade lighting to CBD area to activate the nightlife more than what it is now. This facade light-up works go along with the Open Sydney 2030, which is a strategy for the development of Sydney’s night-time economy. The city is looking for a balance between planning to boost the night-time economy and being sustainable and conscious of energy consumption. One of the most interesting parts we learned from the interview is that the city puts safety as a priority when it comes to the lighting of the city. It sounded that the city has a stringent requirement for light levels in public areas.

George Street, Sydney in 1950

George Street, Sydney in 2019 (at Night)

Queen Victoria Building in George Street, Sydney in 2019

George Street, Sydney in 2019

Sydney CBD roads

From the late 1800s to the 1960s, Sydney had the extensive tram system running along the main roads of Sydney. The trams then faded out in favour of buses from the 1960s to 2015 until Sydney decided to bring back the old tram system back to make more pedestrian-friendly roads. This massive change in the mode of transportation affected the lighting design of CBD roads as well. Following the direction from ‘Sydney Design Code” which was issued in 2015 by the City of Sydney, the design of pole light on the road where light rail runs have changed to accommodate the structural and operational requirements for the light rails such as signage, signalling and overhead wires. The customised light pole design also helps to identify where the light rail is running. During our survey, CBD light rail system was partially operating, and we were able to spot the new pole lights with multiple tiers of light source were installed. The light levels of George street were quite bright at an average of 100lux and mostly cool white (4000K) were used.

Opera House, Sydney

Darling Harbour, Sydney

Entrance of Queen Victoria Building, Sydney

Street lighting design module

In contrast to the lighting design scheme of George Street where the choice of streetlight accentuates modern look of the city, there are many other areas in the city where a rather decorative and historical lighting design module is used. For example, throughout Darling Harbour and Clarke Quay, similar sphere shape pole lights were spotted and in Queen Victoria Building, spherical pendant were used for interior space. Having a similar design language for different parts of the city adds to the sense of continuity in city scale and it was noteworthy to see the continuation of design language between exterior and interior space. We thought that these types of lighting designs come in human scale and add a rhythm to the city nightscape.

Sydney Central Station

Highliy illuminated at Station square

Sydney central staion facade

Grand concourse with blue ambient light

Platform illuminated evenly at 320 lux average.

More than 100 years old station building stands with a dignifying presence while functioning as a core hub of transportation in Sydney. As for its night-time scenery, lighting seems to focus more on providing functional needs. We had found that walkways are evenly lit with a high range of brightness for the general public. Station Square and the approach pathway to the building are illuminated intensively at around 300 lux average. The Grand concourse is lit with blue colour ambient lighting, which again gives a uniform and even illumination to the floor. From the personal and professional point of view, we thought that the architectural features of the heritage station could have been highlighted better, creating a more dramatic and beautiful space. Although it was understandable that crime prevention is a crucial consideration when it comes to lighting design for a station, we could not help but ponder why the platform was having higher lux levels than some of the libraries we visited in Sydney.

Darling Harbour and Streets

Looking at CBD from Prymont Bridge

Darling Harbour waterfront

Not much attention could be captured at the most of street level lighting condition

University of Technology Sydney has very unique buildings

Darling Harbour is one of the most vibrant and bustling areas of the city, and it was by far the most colorful and noisest area at night in the Sydney CBD. However, we noticed that many of the building facades and pedestrian walkways along the harbourside were not lit, and the interior lighting of F&B shops rather generated the night-time mood for the place.

Global Climate Strike (Sept 19, 2019)

It was such a sight to witness Global Climate Strike in Sydney, which have gathered around 50,000 people across Sydney. Organisers want the government and business to commit to a target of net-zero carbon emissions by 2030.

On a side note, under the city of Sydney’s development plan ‘Sustainable Sydney 2030, ‘the government plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 70percent by 2050 compared to 1990s levels. A 10% reduction is possible by adopting more efficient lighting sources.

(Momoko Muraoka)

Tokyo Survey: Tsukuda・Tsukishima

2019.11.18 Kyoko Takubo+Yuichi Anzai+Namiko Watanabe

An overview of Tsukishima. In contrast to the bright large city buildings, the small alleys and storefronts don’t leak much light

Tsukuda is an fisherman island made in Edo-period. Tsukishima was landfilled in Meiji era and now there are still many row houses and small alleys. While the port area of Tokyo is going through mass redevelopment, we investigated the lighting environment of this area filled with intermingling old town houses and large city buildings.

Tsukuda

Tsukuda 1Chome Mainstreet. Children playing outside the old candy store

Tsukuda 1 Chome Mainstreet is mainly lit with mercury lamps

Tsukuda Machikado Museum. Its lit with LED3000K with about 134lx.

Our investigation started by taking an overview photo from a tall building from the other side of the river. With the hustle and bustle bright lights from the Central area’s cityscape, there was one part that was dark- that is our target of this investigation, Tsukuda・Tsukishima. The dark patch from this area is even more pronounced as it is surrounded by the bright city lights all around.

As we get back on the ground, we headed towards Tsukuda 1 chome (Old Tsukuda Island) Mainstreet. On our way we saw the mercury lamp streetlights (4500K) emitting some green tinted white light. The average brightness was around 11lx. In the day you could still see a nostalgic scene with children playing outside the old candy store but as traffic is scarce at night, it eerily silent. The only differing light source was the Tsukuda Machikado Museum at the end of the road. Its display features the festivals special to the region that have continued since the Edo period and the Mikoshi and Lions used in the Sumiyoshi Shrine festival, but our focus was drawn to the space as it was warmly lit with lightbulbs in contrast to the mercury streetlights.

As we explored the area, we found out that a Shrine continued from the Edo-period existed on 1 chome. It hid at the back of a thin alley between two houses, somewhere that would be difficult to find on your first visit, but we had the faint smell of burning incense to help us. The inside was neatly cleaned and brightly lit with fluorescent lights (133lx) which showed us how dearly the locals treated the Jizo statue.

Sumiyoshi Shrine, which also has been protecting this Tsukuda area from the Edo period, welcomed worshipers warmly with two 2700K lights from its new stone lanterns.

Ishikawashima Lighthouse, rebuilt from a lighthouse in built at the end of the Edo period, was lit up at night. While the whole town seemed lit generally with mercury streetlights, I get the impression that the places most important to the locals seemed to be lit carefully.

Because Tsukuda is a residential area, it shouldn’t be a bad thing that there is not a lot of light at night. However, as a historical landfilled area (as compared to the ones around it that were filled in the Meiji era) it shouldn’t be lit with such cold lighting as the green light from the mercury lamps but with a warmer light, or one which design can give us a glimpse into the history of the area. (Yuichi Anzai)

Tsukuda Tendaijizousonn Entrance

Sumiyoshi Shrine

Tsukishima

Nishinaka Shopping street Monja Street

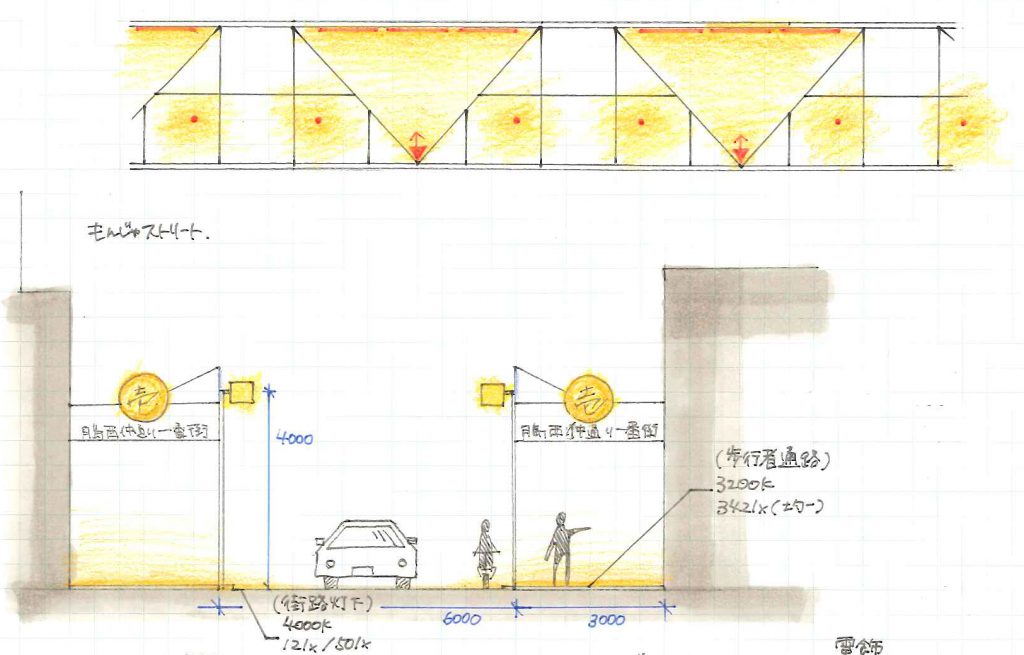

Monja Street Section View

Monja Street Arcade

Town of Monja, Tsukishima was created when Tokyo harbor was landfilled in the 25th year of the Meiji-era. There were many factories in the area at the time and because the workers needed residences many row houses were built in Tsukishima along with small roads that twist and turn around those houses. While the Great Kanto Earthquake and Bombing of Tokyo caused massive changes to the center of Tokyo, the effects were relatively small in Tsukishima, resulting in one of the rare places you can see Meiji era style streets and houses.

In Tsukishima, we focused our investigation Nishinaka Shopping Street, famous for Monja Street, and the winding roads and alleys around it. As we walked into the Nishinaka Shopping Street from the Tsukishima station side, our eyes were caught by the arcade that stretched about 400m. It featured fluorescents, downlights, spotlights placed in a rhythmical pattern. The ceiling that was cut out in triangles, lit with fluorescents, in combination with the round downlights and created a cute pattern that stretched down the arcade. We measured the lights to be at around a color temperature of 3200K and brightness of 340lx directly under the arcade. It seems to have an effect on foot traffic as well, where pedestrians seemed to prefer the bright arcade instead of the middle of the street (which is also paved to be a partial pedestrian zone). The arcade also featured blue and white fairy lights, perhaps Christmas decorations that alternated colors as it ran along the length of the street. Its contrast with the warm light mentioned before caused the cables to stand out which was slightly disappointing.

One step into an alley gave transferred you into a completely different mood, where the lights are much dimmer than the storefronts. The generally dark alley and the light spilling from the restaurants and bars and their colorful signs creates a light-scape that entices you to explore deeper into the alley. The bars in the alley had relatively more locals in contrast to the tourist centered storefront street. The view of locals drinking and eating together happily after work brings us back to Tsukishima’s roots as a worker centered residential area. (Namiko Watanabe)

Monja Street Back alley

A Motsu Grill store in an alley

Conclusion

Construction on a new High-rise apartment has started on the east side of Nakanishidoori 2nd Street. The lower floors of the place, facing Monja Street has plans to be turned into Row house style stores. This makes us feel that while the buildings around the area change, the storefront street would be relatively untouched and made to remain as a tourist attraction. But it still makes us question what will happen to the unique alleys, row houses, and the culture that the locals have cultivated living in the conditions for years.

One thing that is for certain is that the environment here is going to keep changing, and whether something that has been passed down till now stays or changes will likely be decided in the near future. Even if other changes happen, we hope that the parts that make this place unique and therefore interesting remained unchanged with time.

(Yuichi Anzai)