Date of Issue: June 18, 2025

・Activity 1/ City Night Survey: Chandigarh, India(2025.01.15-01.19)

・Activity 2/ City Night Survey: Hida Furukawa, Furukawa Festival (2025.04.19)

・Activity 3/ Night Walk Vol.76: Tachikawa(2025.04.25)

・Activity 4/ Round Table Discussion Vol.73: Review on Tachikawa(2025.05.27)

City Night Survey: Chandigarh, India

2025.01.15-01.19 Masafumi Yamamoto + Yuichi Anzai

About 65 years ago, a vast area at the foothills of the Himalayas was divided into districts for government functions, commerce, education, and residences, with separated roads, creating a landscape completely different from other Indian cities. This survey takes a multifaceted approach to examine Chandigarh’s urban lighting and nightscape, while observing the natural light expressions inspired by Le Corbusier’s architecture.

■Light Rays

First, I quote the words of Le Corbusier:

“Chandigarh is planned on a human scale. It connects to the infinite universe and nature. It is a place for all human activities where citizens can live a rich and harmonious life. Here, the radiance of nature and the heart is within our reach.”

A vast paved ground is moistened by a dense white mist. About 180 meters ahead from where I stand, the High Court building faintly appears. Its enormous facade faces east and west. The sky behind peeks from beneath the portico, and the rays of light passing through it gently caress the huge concrete pillars painted red, yellow, and green, casting the morning sun on the ground. In this city, I encountered several lyrical daylight scenes. I believe this is because the philosophy of Atelier Le Corbusier in Paris, who designed this Capitol Complex, also extended to the urban layout. Until now, Chandigarh has been discussed mainly from an architectural viewpoint. However, I feel it has not been explored much from the perspective of urban lighting. In this survey, while observing the traces of natural light, I want to consider its merits and demerits.

■Door

The architect’s vision of natural light can be read from the legislative assembly building located about 450 meters opposite the High Court. This building features a tower on its rooftop formed by hyperbolic curves, inside which lies the parliamentary chamber. To the left of the tower is a structure modeled after the Jaipur sundial and observatory. Le Corbusier’s approach to astronomy is also reflected in a large enamel mural that serves as a door panel. This enormous door mural consists of 55 enamel plates arranged vertically, measuring about 7

meters in height, 0.7 meters in height per plate, and about 1.4 meters wide. It depicts a lush, vibrant land where humans, animals, and plants coexist, overlaid with multiple planetary orbits in the sky above. Upon close observation, the central theme is revealed to be the sun. The large arch near the top center represents the sun’s path in summer, while the lower, near-horizon path depicts the winter sun. On the left edge, the sun, earth, and moon are illustrated. On the right edge, the solstices and equinoxes—summer solstice, spring and autumn equinox, and winter solstice—are shown across two enamel plates. This grand, weighty door mural can be seen as Le Corbusier’s diagram of natural light. The door itself might symbolize the gateway to understanding this city.

■Shadow

Could Le Corbusier’s deep reverence for natural light have ultimately taken shape as the brisesoleil, a solution to reconcile the harsh Indian climate with inviting light into interiors? The Tower of Shadows standing beside the legislative assembly seems like an architectural husk—its entire structure exposed to the wind, continually responding to the changing seasons, weather, and the sun, casting shadows that shift in expression moment by moment.

The brise-soleil was also incorporated into the house of Pierre Jeanneret, Le Corbusier’s cousin and collaborator, which Le Corbusier used as his studio during his time in India. There, too, soft natural light filtered through, embodying the very essence of this architectural philosophy.

■The Palette of 63 Colors

Le Corbusier developed a palette of 63 colors in collaboration with a wallpaper manufacturer, and he used these extensively in his architecture. For instance, the green-painted exterior walls on the first floor of the Villa Savoye blend into the forest behind, and the natural light, blocked by the eaves, casts shadows that give the building a sense of levitation. I believe that in his architecture, color and natural light are inextricably and purposefully linked.

Here in Chandigarh, too, Le Corbusier must have imbued color with meaning. The fact that the enamel mural on the doors of the Assembly Building is rendered in the same red, yellow, and green tones as the pillars of the courthouse is surely no coincidence. Perhaps, during his travels across India, he discovered a distinct palette—possibly inspired by roadside red walls, ochre earth, or the fiery green of roadside trees. Could it be that he introduced these vivid colors into the otherwise inorganic landscape of the Capitol Complex?

One of the museums Le Corbusier designed stands here in Chandigarh. Color has been applied to the walls where light streams through the brise-soleil and skylights. By applying color to such critical points in a building, he captured the elusive quality of natural light and used it to imbue his spaces with boundless depth.

■Waterfront

In the mid-1950s, a chair known as PH28 was designed for administrative facilities. Made of teak wood with distinctive V-shaped legs and woven cane, it is a notable piece. The designer, Pierre Jeanneret—who also participated in the development of Chandigarh’s districts—is an indispensable figure when discussing the city. There’s something endearing about the photo of him and Le Corbusier floating on Sukhna Lake in a handmade boat. The artificial lake, created as part of the urban plan, was envisioned as a place of relaxation.

Two guidelines apply to this area: first, motorboats are prohibited on the lake; second, vehicles are not allowed on the promenade. These rules are still respected today, helping to preserve a peaceful and refreshing waterfront landscape, away from the city’s noise.

Along the promenade, sturdy concrete garden lamps—about 600 mm in height—are installed at 10-meter intervals. These lamps have been in place since Chandigarh was first established. Their color temperature is around 5000K. As one walks along the path, the orderly arrangement of the lamps gradually dissolves, evoking a sense of astronomical rhythm. They seem to emerge naturally from the heavy, raw concrete aesthetic that defines the cityscape—quintessentially Chandigarh.

The waterfront at night is lively. Light connects the city to the water, and the moist night breeze flows along the promenade. This is a space where people gather to talk, reflect, and share their thoughts.

■Open Hand

I would like to mention a scene I witnessed at sunset in Sector 17, the most vibrant district of this city. It was the sight of a small fire lit by homeless individuals beside the pillar of a grade-separated intersection. The flickering flames illuminated their faces and bodies. I hesitated to approach and instead took a photograph from a short distance away. This moment made me realize that an urban nightscape cannot be described solely with beautiful words.

What Le Corbusier envisioned in Chandigarh was the image of an ideal city. However, in reality, the people originally living in this area were displaced, leading to the formation of slums within the city. In other words, the city has moved forward bearing the weight of inequality atop the architect’s dream. The Open Hand monument, a symbol of the city standing in the Capitol Complex, was completed in the 1980s after Le Corbusier’s death. It was meant to represent a gesture of giving and receiving freely. Le Corbusier never witnessed the city’s completion. What would he think of its present state?

The lights kindled by the people living in the city—whether the elegant garden lamps of Sukhna Lake or the fire beside the flyover pillar—are all indispensable elements of the nightscape. There is no hierarchy between them. The raw realities that arise in areas beyond the reach of lighting design may, in fact, hold the true essence of an urban nightscape. And light reveals the lives of the people who dwell in that place.

If, in the future, we move toward creating a new urban nightscape—one that is overly high-tech, stimulating, and devoid of humanity—I would choose to criticize it. But perhaps it takes several decades after a city or lighting plan is completed for it to mature. That is what I felt during my time in Chandigarh. This city still holds poetic scenes of light. It is likely because the urban environment here is not purely driven by functionalism, but instead retains the richness of India’s vast and expressive climate. (Masafumi Yamamoto)

at the base of a pedestrian overpass

■Sector 17

Sector 17, located at the heart of Chandigarh, was planned as the city’s economic and commercial hub. Upon entering the area, one is immediately struck by a sense of contradiction—simplicity and clutter, decay and vibrancy coexisting—creating a mysterious atmosphere unlike that of any other city.

The area features rows of industrial, four-story buildings lined with concrete columns that evoke a sense of a bygone era. These structures stand neatly on either side of a main street approximately 50 meters wide. Pedestrian and vehicle paths are clearly separated, making it easy to navigate. With many open sightlines, the surrounding buildings and shops can be easily seen from the main road or plazas, reinforcing the sense of a deliberately planned shopping district.

The lower levels of the buildings are occupied by a wide variety of stores, ranging from local businesses to internationally popular brands, and were bustling with shoppers. The contrast between the minimalistic urban design and the shops’ efforts to stand out was striking and fascinating. Displays piled high, colorful signage, and eclectic lighting—downlights, floodlights, bare bulbs, even tape lights wrapped around pillars—gave the streets a lively energy.

As I walked through the area, I could sense the shops’ energy radiating from all directions. Even within the orderly, meticulously planned urban environment, there was a strong presence of the individuality and vitality of the local people of India.

■Main Roads

Streetlights approximately 10 meters in height with a color temperature of 5000K are spaced every 30 meters along the main arterial roads running north–south through Chandigarh. Normally, such sharp beams of light would be piercing to the eyes, but here they diffuse outward, illuminating not only the street trees but even the air above. The fine particles in the atmosphere act like a diffusion lens, making the entire airspace appear to glow—as if the light had taken on mass.

The grid-pattern road system crossing east–west and north–south is one of Chandigarh’s distinctive features. Dedicated lanes are provided for pedestrians, bicycles, and cars, promoting walking and cycling as means of transportation. On the sidewalks, streetlights about 3.5 meters high illuminate the pavement at about 25 lux at night. Though these, like the main road lights, lack shielding and produce glare, the densely growing tropical street trees help protect pedestrians’ eyes, allowing them to experience a shower of light similar to sunlight filtering through leaves. In this environment where air pollution and light pollution coexist, Chandigarh’s nighttime roads exhibit a unique lighting character.

■Summary

In this survey, we had the opportunity to speak with Mr. Pradeep, former dean of Chandigarh College of Architecture and an active lighting designer. Through our conversation, we not only learned about Le Corbusier’s thoughts on natural light but also gained insights into the artificial lighting he designed. For example, the garden lights at Sukhna Lake directly illuminate the curved concrete facades while gently casting light onto the ground. At the Legislative Assembly, there are tall cylindrical uplights—taller than an average person—that serve both functional and decorative purposes. Additionally, light sources were installed even in the skylights, ensuring natural feeling illumination indoors even under low sunlight conditions.

What was particularly striking was how all of these lighting strategies focused on indirect light, with minimal visibility of the actual light sources—effectively controlling glare. It became clear that even decades ago, there was a conscious effort to create eye-friendly lighting environments, where the light itself enhances the architecture and landscape without drawing attention to its source.

How does the artificial lighting of present-day Chandigarh compare? Streetlights brightly illuminating vast areas, lively signage, and floodlights outside shops—perhaps these are not in line with Le Corbusier’s ideal vision of light. Still, within the meticulously planned and well-organized urban layout, we saw a vibrant blend of local life, culture, and natural environment.

Le Corbusier is said to have embodied his human-centered rational design and harmony with nature in Chandigarh: spacious areas, logical road systems, and simple buildings that skillfully utilized natural light. Through this survey, we experienced a city where functionality and beauty coexist—and we also witnessed the vibrancy of local life, which cannot be confined by architectural rationalism. In that sense, Chandigarh has not strayed far from Corbusier’s vision of an ideal place for human living.

More than half a century since its construction, the architecture and cityscape continue to be cherished and protected by the local residents. Grounded in Corbusier’s ideals, how will this modern city of the 20th century continue to evolve in the years ahead? (Yuichi Anzai)

City Lighting Survey: Hida Furukawa, Furukawa Festival

2025.04.19 Hikaru Kimura + Noriko Higashi

When we first held a workshop in Hida Furukawa in 2023, city hall staff told us just how deeply the people of Furukawa cherish their festival. At the Hida Furukawa Festival Exhibition Hall, we were given explanations about the history of the festival and the stalls. We also had the opportunity to see the storehouses where each neighborhood keeps its stall, as well as the lantern stands placed in front of individual houses. This inspired us to head to Furukawa with the intent of exploring and documenting the festival scenes that are so important to the local people.

The Furukawa Festival, held annually on April 19th and 20th, is designated as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage and a National Important Intangible Folk Cultural Asset of Japan. It’s a community-wide celebration so deeply rooted in the town’s identity that even former residents living outside the area for school or work return home specifically for the festival. The event centers around two main elements: the “Okoshi Daiko,” a ritual where a giant drum is paraded through the town and beaten throughout the night, and the “Yatai Procession,” where each neighborhood pulls its own stall through the streets.

When we first visited Furukawa in April 2022 for a workshop, it happened to be just after the festival had ended. The excitement had slightly faded, and the town was in the midst of cleanup. During that time, we were guided by the mayor through the Hida Furukawa Festival Exhibition Hall, where we learned about the festival’s history and viewed actual festival floats. We even tried drumming the Okoshi Daiko ourselves and toured the storehouses where each neighborhood keeps its float. Everywhere we went, we could feel how deeply the people of Furukawa care about their festival. Even as first-time visitors, it was easy to understand how central the festival is to this town. We also learned about how the town’s two sake breweries play a key role in the festival and community life. Their sake is often used as a customary gift among residents, and during the festival, large amounts are collected and resold at lower prices, creating a cycle of joy and mutual support for residents, local businesses, and the breweries themselves. The festival not only fosters community interaction but also invigorates the local economy, making it an indispensable event for Furukawa.

Inspired by the mayor’s passion for the festival and the omnipresent traces of its significance throughout the town, we were eager to witness it firsthand. As soon as we received an official invitation from the city, Kimura and I immediately decided to take part in the festival. (Noriko Higashi)

The nighttime festivities take place from around 8 PM until midnight. Everyone first gathers at a location known as the Festival Square (Matsuri Hiroba). At the center is the “Okoshi Daiko”, a massive drum mounted on a tower large enough to carry people. Surrounding it are “Tsuke Daiko”—smaller drums attached to wooden poles—carried by participants from each district. Once the festival begins and the Okoshi Daiko sets off through the town, the various groups follow, vying to get as close to it as possible. Being nearest to the Okoshi Daiko is considered a great honor, so each group shouts out their team names and jostles with others as they proceed. This lively competition is known as “Furukawa Yancha” (“Furukawa Roughhousing”), and although in the past it was said to get quite heated and wild, Furukawa remains an impressively safe and orderly town—this kind of festival seems to foster a strong sense of unity among its people.

Before the “Okoshi Daiko” departs from Festival Square, a performance known as “Tonbo”(“Dragonfly”) takes place. Atop the wooden poles holding the “Tsuke Daiko”, participants climb up and strike a dramatic pose with their arms and legs spread like a dragonfly. One might assume this is part of a sacred ritual, but it actually originated when someone began doing it out of boredom during the waiting time—now it has become a crowd-pleasing tradition, with each district’s young men taking turns to perform.

Given the towering “Okoshi Daiko” and the elevated “Tonbo” performances, lighting that illuminates from above is essential. Temporary white floodlights are set up on existing tall poles and on top of a structure called the “Otabisho” (a sacred resting place for deities during festivals).

Before the festival began, the visibility of these floodlights felt a little disappointing. However, once the event was underway, they effectively illuminated the height and energy of the Okoshi Daiko and the “Tonbo”, highlighting the brilliance of the participants’ white “sarashi” sashes and enhancing the overall atmosphere. The brightness and positioning of the light sources felt wellsuited for the energetic start of this festival.

to perform the “tonbo” (dragonfly pose)

Once the “Okoshi Daiko” departs from the Festival Square, townspeople carrying lanterns lead the way, with the “Okoshi Daiko” following behind. Each person carries a long pole tipped with a redand-white paper lantern. What was truly surprising was that inside every lantern burned an actual candle flame. Seeing such a large number of children and adults walking with lanterns in hand made it clear how much the townspeople look forward to the festival.

Among the crowd were also large lanterns representing each group, some attached to bamboo poles about three meters tall. Unlike the smaller lanterns, the movement of their light and their color seemed different, so we speculated they might be using LEDs. However, one of the bearers noticed our curiosity and kindly showed us the candle inside. It was a traditional “wa-rōsoku” (Japanese candle), thick with a large wick, providing a long-lasting, stable flame. The smaller lanterns used the more commonly seen thin candles, and while their flame color appeared similar, the difference in hue might have been due to the type or thickness of the washi paper used in the lanterns.

As a side note, the lantern I was carrying had a poorly fixed candle inside, which tipped over and caught fire. Only one other person and I seemed to experience this, and even children handled their lanterns with such ease that there was no real sense of danger—it was clear the townspeople were quite accustomed to this tradition.

Lighting each candle with care is itself a sacred act, symbolically receiving fire from the gods, and it greatly enhances the festive atmosphere and emotional excitement. I felt that this ritual, too, was an essential element of the festival’s lighting. I was deeply moved by how the people of Furukawa cherish every detail in this way.

and shadowed without illumination

After the “Okoshi Daiko” left the Festival Square, although many people were carrying handheld lanterns, the tall drum itself appeared somewhat dim and sunken in the dark. It felt like such a missed opportunity not to fully showcase the impressive sight of the “Okoshi Daiko” moving through the beautiful townscape. At one point, someone’s camera flash lit up the scene, and the “Okoshi Daiko” floated momentarily within the sea of lanterns. That brief flash captured a bold and striking image of the drum, and I thought it might be interesting if there were a path of light that illuminated the “Okoshi Daiko” at key moments—like a “hanamichi” on a stage. Since this is a night festival, light plays a major role, for better or worse, depending on the timing.

These days, culture and history are often preserved in a more formal, static way. But in Furukawa, the festival is cherished because the townspeople genuinely look forward to it. That spirit may come from the way they treat even a single candle with care. I sincerely hope that this townscape—one that the townspeople can love—continues for many years to come. (Hikaru Kimura)

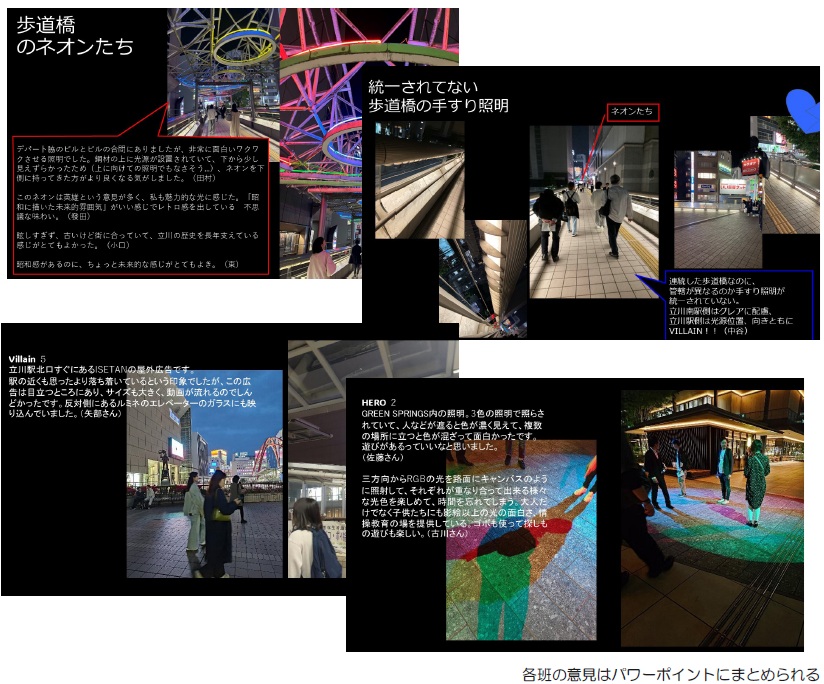

City Night Walk Vol.76: Tachikawa

2025.04.25 Shinichi Sakaguchi + Naoko Oguchi + Noriko HIgashi

The enormous terminal station of Tachikawa, with a combined daily ridership of about 410,000 passengers on JR and the Tama Toshi Monorail. The Lighting Detectives had visited Tachikawa in 2021 for a small-group night walk survey on a rainy day with just three people, but this time we decided to revisit with a larger group. This survey focused on the differences between the north and south exits of the station.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, the small-group night walk survey in Tachikawa took place just after the large-scale development GREEN SPRINGS had opened. The live commentary showed scenes of walking from there. Due to the pandemic, there were almost no people around, giving a somewhat quiet atmosphere, but many expressed interest in visiting the calmly lit landscape there. We also wanted to investigate the bustling Friday night around Tachikawa Station, which ranks third in ridership after Shinjuku and Tokyo stations on the Chuo Line rapid service. Therefore, we split the walk between the north and south sides of Tachikawa Station to explore the area.

■Group A: Towards Tachikawa Station North Exit

Group A, led by Captain Mende, conducted a night walk survey mainly around GREEN SPRINGS near Tachikawa Station North Exit. Starting from Tachikawa Station and along Sunsun Road under the Tama Toshi Monorail, there was some surprise at how the vast space immediately near the station is dedicated exclusively to pedestrians. The lighting showed mixed impressions—some fixtures were thoughtfully designed, while others had light sources positioned almost at face height, causing glare. Opinions varied depending on the location.

A few years ago, the large mixed-use complex GREEN SPRINGS opened, and as a new development, it seemed to receive a lot of praise. Especially highly rated were its playful use of RGB lighting and designs that consider nature. In contrast, on the opposite side of Sunsun Road around Tachikawa Fare, there was an impression of more villains lurking. The placement of streetlights was poor, and even among the valuable public art installations, lighting maintenance and upgrades appeared to lag behind.

Overall, this night walk survey revealed many different facets of Tachikawa’s nighttime scene. The city feels like it’s constantly developing, reflecting the flow of the times. Among these, the newest GREEN SPRINGS incorporates various lighting and other thoughtful features here and there, but it felt a bit quiet—perhaps because it was a weekday evening. It seemed like it could be livelier.

On the other hand, the areas around the station with clusters of izakayas (Japanese pubs) and the south exit were noticeably more bustling. (Shinichi Sakaguchi)

of GREEN SPRINGS

スポットライト

■Team B: Tachikawa Station South Exit Area

Team B conducted a night walk survey around the south exit of Tachikawa Station. The area features many pedestrian bridges, sparking a variety of opinions from both heroes and villains alike. First, the large-volume neon lighting was praised as it fit the south exit’s streetscape with a “futuristic vibe imagined in the Showa era,” creating a nice retro atmosphere with just the right brightness—making it a clear hero. It was lighting that everyone really loved.

Around Tachikawa Station, various types of handrail lighting were observed. Among them, the handrail lighting on the pedestrian bridges on the JR Tachikawa Station side had covers to reduce glare, but the brightness was still strong and located at eye level, causing discomfort from glare. In contrast, the Monorail Tachikawa-Minami Station side featured many handrail lights designed with better glare control.

While it’s understandable that lighting approaches differ by jurisdiction, there was a shared opinion that the city could benefit from a bit more consistency in lighting design overall.

paradoxically futuristic

The continuous line lighting installed under the pedestrian deck of the footbridges was first noted for being visually glaring. Additionally, because the lights were mounted perpendicular to the length of the deck, there was an impression that they were excessively bright or more numerous than necessary. Discussions arose suggesting that using glare-free downlights with controlled light distribution to lower the light’s center of gravity, or arranging the line lights parallel to the deck, might create a more comfortable and harmonious space.

Around the south exit, there are numerous dining establishments, each featuring different lighting fixtures and projecting signs, creating a somewhat chaotic lighting environment. Amid this, the GEMS Tachikawa building—a dedicated dining complex—stood out positively. Its lighting design, from the restaurants on the first floor up through the plantings on the top floors, was intentionally calm and unified, creating a visually soothing atmosphere that many participants praised as a lighting hero.

The area north of Tachikawa Station, including places like GREEN SPRINGS, is clean and newly developed, while the south side feels older and more chaotic—but it was overwhelmingly more lively. This contrast revealed that Tachikawa’s charm may lie in its very chaos. At the same time, seeing how few people were around GREEN SPRINGS on a Friday night reaffirmed that simply beautifying an area or improving its landscape doesn’t automatically draw people in. I’m looking forward to seeing how Tachikawa continues to change from here. (Naoko Oguchi)

What surprised me most during this night walk survey was realizing just how large Tachikawa actually is. There are still so many parts of Tokyo left to explore. Half the year has already flown by, but I’m eager to keep discovering new perspectives through our walks. We hope to see many of you join us on future adventures. (Noriko Higashi)

Round Table Discussion Vol.73: Review on Tachikawa

2025.05.27 Momoe Nomura + Noriko Higashi

A follow-up meeting was held to review the night walk survey in Tachikawa conducted in April. Members gathered at the LPA office in Tsukuda and enjoyed lunch boxes while engaging in lively discussion. Plans for future activities were also discussed.

A review session was held at the LPA office to reflect on the night walk survey conducted in April 2025 in Tachikawa, Tokyo. Despite all being within walking distance from the same station, each area of Tachikawa revealed its own distinct character, along with unique attractions and challenges. In particular, the large commercial complex GREEN SPRINGS, located on the north side of Tachikawa Station, was noted for its thoughtfully designed spaces. One especially memorable feature was the lighting on the staircase at the main entrance. The blue light, flowing like water down the steps, created an immersive, cave-like atmosphere when viewed from above—evoking a dreamlike ambiance. Participants also praised the pole lights that used RGB lighting to project overlapping colors onto the ground, turning illumination into an experience rather than merely a visual aid. These elements received high marks for their creativity and attention to user experience.

However, in some parts of GREEN SPRINGS, it was pointed out that certain shops used bright white lighting, which clashed with the otherwise warm-toned atmosphere of the area.Near GREEN SPRINGS, under the monorail, several issues were also identified. For example, lighting on public artworks was overly intense, making it hard to appreciate the details. Additionally, some newly installed LED signage was too bright, making it difficult to read—these elements were considered “villains” in the night walk survey.

At the pedestrian bridge on the south side of Tachikawa Station, the handrail lighting lacked consistency. Despite being part of a continuous structure, the brightness and color temperature varied by location. While the lighting design on the southern stretch was praised for reducing glare, the area closer to the station drew criticism for poor placement and angles of the light sources. When comparing the overall lighting environment of the city, the north side of the station left a calm and organized impression, whereas the south side—crowded with restaurants and entertainment facilities—felt visually chaotic due to an array of mismatched signboards and storefront lights. Some participants even noted concerns about the area’s perceived safety.

summarized and presented their findings

Through this night walk, I realized that well-planned lighting—like what we saw at GREEN SPRINGS—can create spaces that are both attractive and comfortable, encouraging people to stay longer. On the other hand, when lighting is too bright or inconsistent, it can actually diminish the charm of a place. That said, despite the beautiful nightscape of GREEN SPRINGS, the area was sparsely populated, whereas the more chaotic southern side of the station was bustling with people. This contrast made me realize that lighting alone cannot create urban vibrancy.

This experience allowed us to explore various uses of lighting and offered valuable insights into the complexity of urban illumination. The salon serves as a platform for each team to regroup and share their findings after the night walk survey. Even those who cannot join the walk are welcome to participate online, so please feel free to join us. (Momoe Nomura)