2022.06.28 Kouki Iwanaga+ Xiaoyi Dong+ Hikaru Kawata

Yokohama Minato Mirai, which has seen rapid development in recent years with projects such as Japan’s first urban circulation ropeway “YOKOHAMA AIR CABIN” launched last spring, the cruise ship terminal “Yokohama Hammerhead,” and the prestigious Hawaiian luxury resort “The Kahala Hotel & Resort Yokohama.” The purpose was supposed to be to investigate whether the “nightscape of Minato Mirai,” which could be considered a tourism resource in itself, has been well preserved… but.

■Relationship Between Zoning and Street Lighting

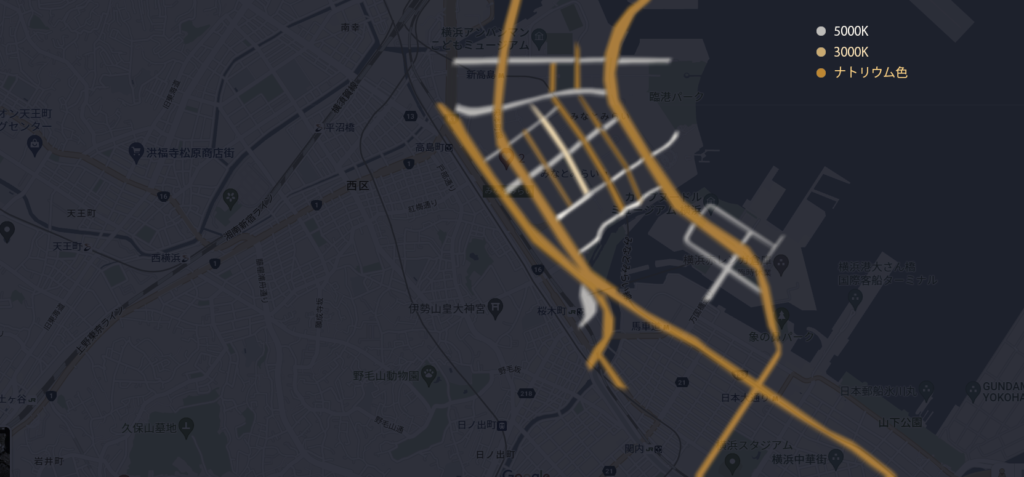

The Minato Mirai area, which was developed on reclaimed land around Yokohama Port, can be broadly divided into three zones: the “Central District,” the “Shinko District,” and the “Yokohama Station East Exit District.” Among these, our survey focused on the Central District—with its high-rise buildings such as Landmark Tower and Queen’s Square Towers—and the Shinko District, which features many commercial and cultural facilities such as the Red Brick Warehouse and Yokohama Hammerhead.

When examining the street lighting in these two districts, it was found that the streets running parallel to the Rinko trunk road and the Metropolitan Expressway were lit with sodium-colored lamps, while the streets leading toward the port, such as Icho Street and Keyaki Street, were illuminated with streetlights at a color temperature of 4000–5000K.

At first glance, this color temperature plan, which changes according to the direction of the streets, appears well-organized. However, according to the building color scheme guidelines for the Minato Mirai area, the Central District is designed with bright achromatic tones, while the Shinko District follows a warm color palette consistent with the red brick aesthetic (Minato Mirai 21 Shinko District Townscape and Landscape Guidelines). Considering this, I felt that aligning the streetlight color temperature plan with the building color scheme would have made the urban landscapes of each district stand out even more. (Xiaoyi Dong)

■Minato Mirai under official energy-saving request

Coincidentally, the day we conducted our survey fell within a period when an official energy-saving request had been issued due to electricity shortages. The newly opened YOKOHAMA AIR CABIN, whose gondolas normally emit light in a variety of colors, was completely dark that night, making it difficult to tell from a distance where it was operating.

In addition, other iconic lighting elements that usually define the nightscape of Minato Mirai were turned off: the illuminations of the Cosmo Clock Ferris wheel, the floodlights of the InterContinental Hotel, the façade lighting of Anniversaire, and the crown lighting of World Porters.

Cosmo World felt rather deserted, so I asked a ticket sales staff member whether the energy-saving measures had affected visitor numbers. The answer was, “There has been no impact due to energysaving.” This may have been because our survey was conducted on a weekday.

From a lighting perspective, even with the major light sources mentioned above turned off, when we measured the pavement illuminance walking from the Central District to the Shinko District, we still recorded around 15–30 lx. This was more than sufficient brightness for walking.

Looking around, there were people lingering quietly along the waterfront, and groups of skateboarders gathering near the Red Brick Warehouse. Local residents did not seem to feel saddened by Minato Mirai’s dimmed nightscape; on the contrary, they may have found the less flamboyant brightness level more comfortable. (Hikaru Kawata)

■How to Create an Energy-Saving Nightscape as a City

While the iconic nightscape elements were turned off, we found that the circular plaza of Grand Mall Park, near Landmark Tower, was illuminated with an excessive 500 lx of brightness—even though nobody was using the space at the time. Furthermore, the luminous columns there exceeded 1000 cd/㎡, glaring so intensely that they almost pierced the eyes. I felt that this kind of unnecessary energy consumption could be redirected into more meaningful lighting elements, contributing to the Minato Mirai nightscape. It also seemed clear that the city needs to review and identify more precisely where energy-saving should actually take place.

Because we began the survey expecting the glamorous nightscape that Minato Mirai is known for, the impact of these energy-saving measures was somewhat shocking. With symbolic lights extinguished, the balance of the nightscape was lost, reminding us that harmony is essential for urban nightscapes. At the same time, in Japan’s ongoing pursuit of decarbonization, the balance between energy conservation and nightscape design will remain a long-term challenge.

Team member Dong commented on the Cosmo Clock’s illumination, saying, “What’s interesting is that when it is off, your line of sight passes through it, revealing the nightscape beyond.” Indeed, while Cosmo World closes at 8:00 p.m., the Cosmo Clock continues to stay lit until midnight for the sake of Minato Mirai’s scenery. Perhaps after 8:00 p.m., it would be better to limit illumination to periodic, time-signal-like moments while leaving it unlit in between.

Because Minato Mirai is still in the process of development and the community is working together to build the city, we hope it will take pride as a future-oriented environmental city and create an energy-efficient nightscape that makes the most of its resources. ( Kouki Iwanaga)