2023.08.02 – 2023.08.04 Yumi Honda+Sachiko Segawa

The theme of this survey is “lighting on boats since ancient times”. Cormorant fishing on the Nishiki River in Iwakuni has been practiced for about 400 years. The Kangensai Festival at Miyajima Island has been held since the Heian period (794-1192). We investigated the relationship between water, light, and people in these two different areas.

■Iwakuni The Light of Cormorant Fishing, an Ancient Fishing Method

Cormorant fishing has been practiced on the Nishiki River in Iwakuni City, Yamaguchi Prefecture, for about 400 years. The cormorant fishing is still enjoyed today by taking a pleasure boat ride from the foot of Kintai-kyo Bridge, one of the three most famous bridges in Japan. The day we visited was a weekday in mid-summer, and the daytime crowds were sparse, but in the evening, people began to gather along from somewhere the riverbank and board the cormorant fishing boats. In western Japan in summer, it is still light even at 18:00. Looking at the sightseeing boats from the bridge, I could see people enjoying a party on the boats with lanterns hanging down. As it gradually got darker and the lights of Kintai-kyo Bridge and lanterns along the river were lit up, we slowly waited for the cormorant fishing time to start.

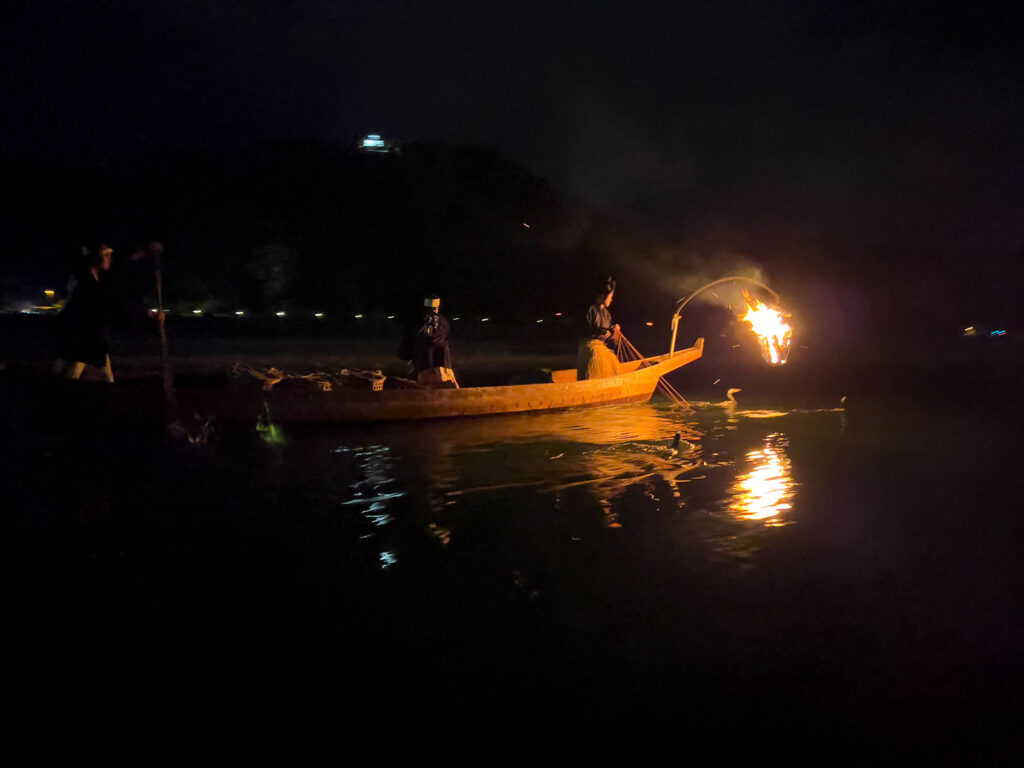

By the time the pleasure boat landed for a break, the sun had completely set and Iwakuni-jo Castle at the top of the mountain was lit up. Finally, it was cormorant fishing time. We boarded the pleasure boat to see the cormorants not from land, but from close up. The Kintai-kyo Bridge was illuminated, but not so brightly, and some of the light was greenish, perhaps due to deterioration of the fixtures over time. There were four 10-meter-long pole lights along the river, each with three discharge spotlights.

There was not much light from the road along the river, and the river was almost completely dark. As we moved a little upstream and waited, two cormorant boats with a cormorant master and a boatman on board came down from upstream with a bonfire burning. Several cormorants tied to reins swam around the boats and fished. The fish often hide behind rocks in the river, so a bonfire is lit to scare them away, and the cormorants catch them as they emerge. The cormorants master watch the fishing situation and light firewood (pine splints) on the bonfire or rotate the bonfire pole. The boat was going faster than expected as it approached, and the bonfire was shaking and sparks were flying. The cormorants master were wearing windbreaking raven hats to protect their heads and eyebrows from the bonfires. The performance was so powerful that you could hear the cormorants and the cormorants’ breathing and feel the heat of the bonfire as it approached. It was a fantastical moment as the light from the bonfire

shimmered on the waves as the boat passed by.

■Miyajima Island The Light of a Magnificent Festival Continuing from the Heian Period

Miyajima Island, located in Hatsukaichi City, Hiroshima Prefecture, is now a popular tourist destination, and was uninhabited until the middle of the Kamakura period (around 1250). Therefore, it is said that people used to travel back and forth from Jigozen Shrine on the other side of the island, on the Honshu side of the island, to attend various events at Itsukushima Shrine. Itsukushima Shrine, now a World Heritage site, is still strongly connected to the sea, not only in its appearance, but also in its festivals. This time, we investigated the lighting of the Kangensai, a festival said to have been started by Taira no Kiyomori. The festival is always held on the 17th day of the 6th lunar month (August 3 this year), as the ebb and flow of the tide is an important factor.

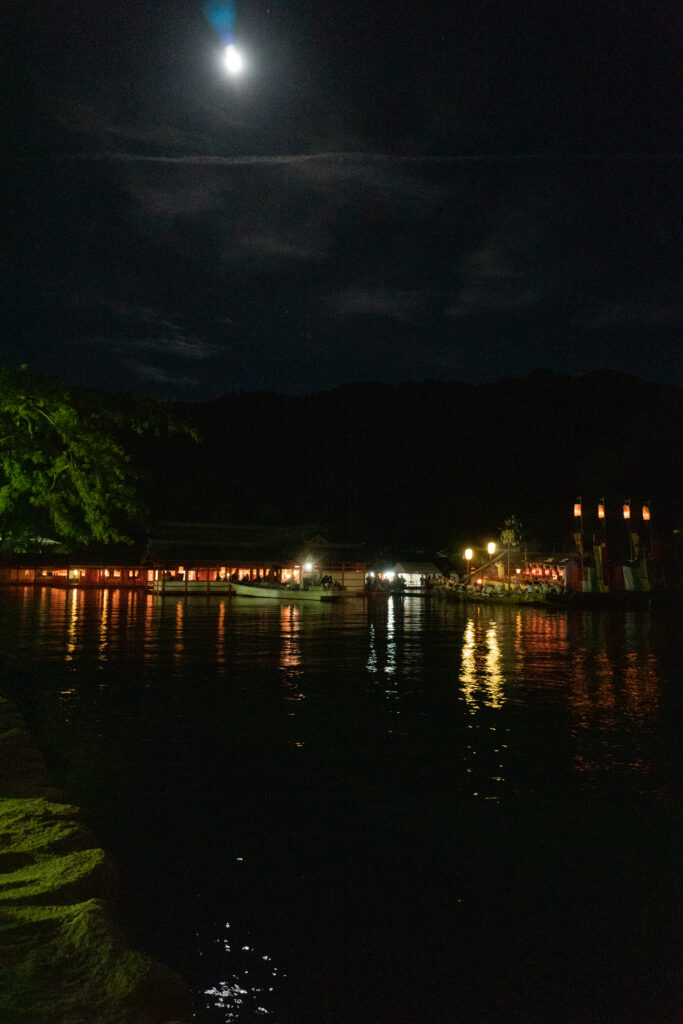

The festival, which lasts until late at night, is far more grandiose than we had imagined, but because it is held over a wide area and deals with the natural ebb and flow of the tide, it is also very open-minded in a good sense of the word. When we arrived at Miyajima Island in the early afternoon, the portable shrines and rowing boats were already anchored off the Otorii, and after 4pm, we watched the portable shrines carried from Itsukushima Shrine pass through the Otorii from the ebb tide flats, board the boats, and rush to the boarding area to follow the festival on the sea in a sightseeing boat. Today, the Goza-bune boats and rowing boats are surrounded by many sightseeing boats, and the sea is congested with boats. I couldn’t help but laugh at the gap between the solemnity of the festival and the view. At this point, the lanterns, snow cave, and bonfire had not yet been lit, but I could hear the rowers’ courageous shouts on the sea breeze. As the sun gradually set and the setting sun reflected on the surface of the sea, the sightseeing boat we boarded turned back to Miyajima Island. Then we headed to Nagahama Shrine on Miyajima to greet the boats that would return in the evening after completing their rituals on the other side of the island. (Sachiko Segawa)

■Nagahama Shrine Lantern procession and bonfire to welcome the boats

The schedule was delayed by another hour due to the tide level, leaving more than enough time for the night. After spending some time at Itsukushima Shrine, admiring the lights of the Otorii (Grand Gate) and the waning sky, and playing with deer, people who had finished strolling the night streets or eating were gathering one after another at Nagahama Shrine after 9:00 p.m. After a few minutes of waiting for the boats, with candlelight in the lanterns and yes fixed on the dark surface of the sea, the boats begin to drift by. From a distance, the sounds of the rowing boats’ heroic taiko drumming and ondo, and the elegant sounds of gagaku (ancient Japanese court music) can be heard, and when the faint lights of bonfires and tall lanterns come into view, the lanterns swaying in the air welcome the boats. When the boats arrive at the torii gate facing the sea, the gods visit the shrine through the boundary that is placed from the torii gate to the shrine. During this time, the air was quiet, and we listened to the sound of the waves and the kangen music playing on the boat. When the greetings to the shrines were over, they made a three-phase bow in front of the torii gate and headed for the next shrine. After the ship left, a lantern procession was held to the side of the main shrine. It was as if I went back in time as the lanterns of slight illumination that illuminated my face only a little moved along the road at night in dots. At this point, it was 11pm. The time passed more slowly than usual. One might imagine that a festival would be lively with food stands and stalls until nighttime, but during the Kangensai, Miyajima was open for regular business and most stores were closed in the evening.

However, the lanterns in front of the stores and the eaves of the houses were lit, creating a quiet but special evening.

along the seawall were an ethereal sight.

■Itsukushima Shrine : The corridor sinking at high tide and the return of the main shrine

Other than the festival, the other point of investigation was the lighting up of

Itsukushima Shrine and the Otorii (Grand Gate) at night. From dusk, many people gathered on the beach overlooking the torii gate. As night falls, the tide gradually rises and the illumination of the torii gate is reflected on the surface of the sea. The vermilion-colored Otorii gate, which had been repainted after a major renovation, contrasted vividly with the blue sea sky during the day, but at night it seemed subdued against the blackened background. Tonight, the main shrine is set up for a festival. The lanterns hanging in the corridor were only faintly bright compared to the size of the lanterns, and their dim light was so weak that one could barely see one’s feet. It was a stark contrast to the glamor of the usual illumination, with vermilion light leaking out from inside the corridor. We visited the shrine before going to Nagahama Shrine, but when we returned near the main shrine after 11pm, the corridor was flooded by the high tide. The lights of the lanterns reflecting on the water and the empty corridor seemed to amplify the sacred atmosphere. The sound of the Hichichiriki reed could be heard from nowhere, and people’s anticipation for a glimpse of the return of the boat was heightened. When the date changed, the rowing boat and the boat slowly passed through the Otorii Gate. The boats would normally have proceeded as close as possible to the shrine pavilions, but due to the tidal conditions, the boat towing was performed at a distance from the shrine pavilions. The oar handling of the rowers, who had pulled the boat by hand, and the daiwari, or the dance of the rowers as they shook themselves to the beat of Japanese drums, were all very brave, and the audience applauded the rowers as they pulled the boat around up close. Afterwards, the boat approached the shrine and a prayer and orchestral music were performed. It was around 1am when the shintai (an object of worship housed in a Shinto shrine and believed to contain the spirit of a deity) returned to the shrine pavilion. Because of the long hours of the festival, at first I could not decide how much to investigate. However, the innkeeper told us about the highlights of the festival, and we were able to participate almost the entire time, which was a good experience for us to fully appreciate the flow of time and the atmosphere of the festival. Normally, when the imperial carriage returns to the main shrine, visitors are allowed to touch the phoenix, which is said to be quite an exciting event. I would like to participate in that part of the festival the next time I have the chance.

■Summary

This time, under the theme of “lights on boats,” we conducted surveys at two locations facing the Seto Inland Sea. The same form of lights had completely different aspects: dynamic and static. The lights of cormorant fishing in Iwakuni now play a major role as a tourist resource, but they are deeply rooted in daily life, and their lively lights remind us of the powerful activities of the cormorants and the people who chase the fish. The lights of Miyajima Island’s Kangen festival were a beacon across the sea at night, and one could sense the festive nature of the ritual solemnly performed. Although it was a full moon at high tide, the darkness of the night on the boat and at the seaside was deeper than expected, and the heat of the bonfires, the sound of exploding flames, and the lights flickering on the pitch-black surface of the water sharpened my senses more than usual during the two nights. We would like to conduct another survey in a different area so that the traditional boat lanterns will be handed down in the future. (Yumi Honda)