2018/10/13-23 Mikine Yamamoto + Kouki Iwanaga

This was our first South American survey in about 15 years. We tracked the light expression of Rio de Janeiro, a port city marked by both entertainment and poverty, which hosted the FIFA World Cup in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016 and has become increasingly international. While possessing famous coasts like Copacabana and Ipanema and being counted as one of the world’s three most beautiful harbors, it also has the “favela” slums covering its hillsides. Surrounded by magnificent nature, Santiago, Chile’s largest city, has annual rainfall of only about 360mm, meaning it is sunny for most of the year. We investigated the lighting situation of this city blessed with natural light.

The nightscape from Pão de Açúcar: A beautiful contrast created by the rich topography

Viewing Copacabana Beach from Pão de Açúcar

Viewing Copacabana Beach from Pão de Açúcar  Favelas built on the mountain slopes

Favelas built on the mountain slopes

■Rio de Janeiro / Brazil

Rio de Janeiro is an international tourist city that hosted the Carnival and the Olympics in 2016. It is said to be a microcosm of the country, where light and darkness coexist: scenic areas with beautiful topography blending nature and culture are situated next to slums. We surveyed the light expressions of this city, which has various faces, including the glamorous light of tourist and resort areas, and the strangely glowing light of the favelas (slums) where poor communities gather, reflecting the lives of the people.

The suburbs leading from the airport to the city center have a typical streetscape, similar to those in China or other parts of Asia, and abandoned-looking buildings are prominent. A notable feature is the huge number of small buildings (favelas) that completely cover the mountain slopes, creating a unique landscape. In Centro (the old town), historical and modern architecture coexist, and there are streets, squares, and buildings that were redeveloped for the Olympics. Copacabana Beach is lined with hotels and restaurants and is bustling with tourists. The overall atmosphere of the city, perhaps due to the bad weather, was completely devoid of the cheerful, passionate feeling we had imagined.

■Nightscape Emerging in the Valley

Pão de Açúcar (Sugarloaf Mountain) is the iconic rocky mountain that defines Rio de Janeiro’s nightscape as it juts out into Guanabara Bay. From its 400-meter-high summit, you can see the entire city of Rio de Janeiro, nestled between the mountains and the sea. The deep valleys of the rugged mountains are tightly packed with buildings, creating a stunning urban view shaped by its unique topography. As evening progresses, the mountains and sea fade into shadow, and the city’s lights emerge. The overall impression is one of low light, mostly composed of streetlights and window lights, with no buildings featuring garish illumination. The lights of the favelas (slums) blanket the mountainsides, their dense, fine points of light creating a three-dimensional, slightly mysterious atmosphere of life. The beach lighting is notably bright and catches the eye, its reflection on the ocean surface emphasizing the beautiful curve of the coastline—a signature feature of Rio de Janeiro’s nightscape. With better weather, the Christ the Redeemer statue on Corcovado Hill would have been brilliantly illuminated, offering an even more iconic view, but unfortunately, we couldn’t see it from the city at all during this trip.

The beautifully curving Copacabana coastline.

The beautifully curving Copacabana coastline.

Copacabana bars bustling with foreign tourists.

Copacabana bars bustling with foreign tourists.

Carioca Street where there is no sign of people

Carioca Street where there is no sign of people

The Light-up of the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Theater

The Light-up of the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Theater

The plaza in front of the Municipal Theater. The number of pole lights is extremely high

The plaza in front of the Municipal Theater. The number of pole lights is extremely high

Museu do Amanhã. The exterior wall with solar panels installed

Museu do Amanhã. The exterior wall with solar panels installed

Rodrigues Alves Avenue (Daytime)

Rodrigues Alves Avenue (Daytime)  Rodrigues Alves Avenue (At night)

Rodrigues Alves Avenue (At night)

At night, the lively atmosphere of the day completely disappears, and the streets become quiet with no sign of people. Police vehicles are stationed in various places, and their lights are extremely conspicuous. In the old town (Centro), historically important buildings and churches are lit up. The technique is common, where floodlights are installed on the streetlights for the roadway to uniformly illuminate the entire building. In the downtown area, shops are closed and there are no people around. There are no sign lights whatsoever, and only the roadway streetlights illuminate the buildings. In the park within the development district, which was redeveloped for the Olympics, a large number of pole lights were installed, making it a very bright park with an average of over 30 lux.

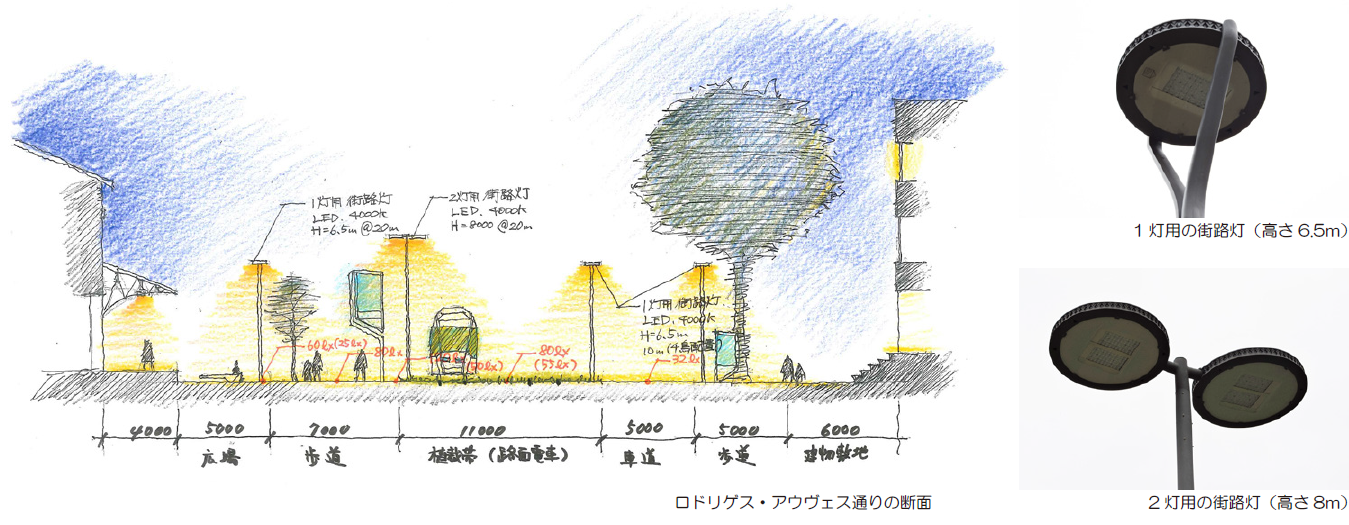

Rodrigues Alves Avenue was also developed for the Olympics, resulting in a comfortable space that is 23 meters wide and offers clear visibility. The center of the street is a planting strip where a modern tram runs, and both sides are separated into a roadway and a pedestrian space. LED streetlights are used, and the design of the two types of streetlights is unified. In the 7-meter-wide pedestrian space, 8-meter-high, two-fixture lights are placed at a 20-meter pitch on the central planting strip side, and 6.5-meter-high, single-fixture lights are placed at the same pitch on the building side. The illuminance in the center of the pedestrian space is 80 lux, and 25 lux in the darkest areas, making it extremely bright. The buildings along the street are offices converted from warehouses and are lined up continuously. Since the walls are illuminated, there is a sense of brightness, creating a very comfortable space. The roadway side has a staggered layout of 10-meterhigh lights, with an illuminance of about 35 lux in the center of the road.

The urban lighting in Rio de Janeiro has become light aimed at preventing crime by making things bright. Because we couldn’t feel the presence of people, there was no sense of ease or safety; an air of tension permeated the area. I was reminded that the beauty of a nightscape is truly created by the people active in that place and the atmosphere they generate. (Mikine Yamamoto)

■Santiago / Chile

Santiago is the largest city in Chile, surrounded by the Atacama Desert, the Patagonian Ice Field, Aconcagua, and the vast Pacific Ocean. With climatic conditions that bring over 300 sunny days a year, we investigated the relationship between the city and its natural light. We also surveyed the urban lighting conditions of Santiago—a major city that still offers tranquility with its many museums dedicated to pre-Columbian artifacts and its abundant nature, such as forest parks—as well as the interest in light shown by the people who live there.

The Sky Costanera Center, the tallest building in South America, with Aconcagua towering in the background

The view from the Sky Costanera Center. The old town is on the left, and the new town is on the right

The view from the Sky Costanera Center. The old town is on the left, and the new town is on the right

Spotlights used to illuminate the ornamental pillars of a historical building

Spotlights used to illuminate the ornamental pillars of a historical building  Illuminating the building’s structure with floodlights to make the entire building glow

Illuminating the building’s structure with floodlights to make the entire building glow

■Light of the Old Town and Light of the New Town

Looking down at the Santiago cityscape from the observation deck of the Sky Costanera Center—at 300 meters, the tallest building in South America—there were two distinct expressions of light. One was the old town, scattered with the warm glow of sodium streetlights, and the other was the new town, bathed in 4000-5000K light that uniformly illuminated the streets cutting through the highrise buildings. Walking through the streets, we observed that the old town often used external illumination to light its historical buildings, while the new town featured modern facade lighting that illuminated the buildings from within.

■La Moneda Palace and the Entel Tower

When we visited the famous La Moneda Palace at night, we were surprised to find that, unlike other tourist spots, its main facade was not illuminated at all. The Plaza de la Constitución behind the palace had no lighting fixtures within the plaza itself; instead, the entire space was uniformly lit by 15-meter-high floodlights. The light level was about 0.2–0.5 lux on the ground and about 2.0 lux on the vertical plane,

with enough lateral light spill to faintly illuminate the palace’s rear exterior. Across from the palace, a huge Chilean flag was waving in the night breeze, lit by uplights from the ground, which conveyed a sense of dignity. However, when the surrounding buildings were illuminated by the intensely colorful signage lighting of the Entel Tower, which stands about 300 meters away, even the accompanying Santiago lighting designers and students expressed disappointment. It seems that the shared value of distinguishing between what should be lit and what should not, and the discomfort with the aggressive brightness of signage lighting, is common in Santiago as well.

■Santiago’s Blue Moment

Santiago, which was entering early summer with its Mediterranean climate, had a long blue moment, lasting from 7:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. In the evenings, the city was filled with people enjoying happy hour at the open-air terraces. While LED streetlights were widespread in the old town, many had a color temperature of 3000K or lower. I felt this might reflect the aesthetic sense of the people of Santiago—slowly savoring the blessings of nature under the warm-toned light that looks beautiful against the blue moment. (Kouki Iwanaga)

The Moneda Palace facade, standing solemnly in the darkness

The Moneda Palace facade, standing solemnly in the darkness

The brightly illuminated Entel Tower and the lit-up Chilean flag with strong luminance

The brightly illuminated Entel Tower and the lit-up Chilean flag with strong luminance

People enjoying happy hour

People enjoying happy hour